Landscapes and cityscapes were handy subjects for early photographers. But they were at a disadvantage compared with painters: The standard cameras could take in only part of a scene, since few lenses had' a viewing angle exceeding 40 degrees. When a photographer wanted a view of a city or mountain range he had to take overlapping views and paste them together.

In 1844, however, Friedrich von Martens, an engraver-photographer living in Paris, built a camera that could take scenes like the one shown below, embracing an arc of 150 degrees. The secret was a swiveling lens, which swept around a scene, "wiping" a continuous image across a daguerreotype plate five inches high and 17,5 inches long.

In later years similar panoramic cameras were used for pictures of large groups of people like the student body of a school. Some of the results contained a bizarre element, for a fleetfooted prankster could get his likeness into the same picture twice by outracing the camera's panning mechanism. After being photographed at one end of the group he ran around to be snapped again at the other end.

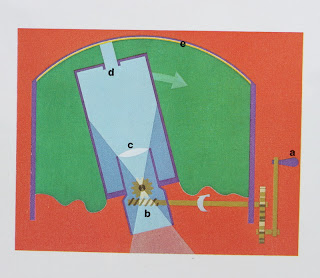

The von Martens camera was the first to use a swiveling lens and a curved plate, devices used in the later panoramic camera pictured at far left. In the von Martens instrument, a hand crank (a) turned a gear (b) that swiveled the lens (c) in its flexible leather mount; in the later camera the lens was moved by turning the viewfinder on top. The lens had a mask with a slit (d) to restrict the image projected onto the plate (e) to a narrow strip; as the lens turned, the strip image moved across the plate, building up the picture in much the same way that a focal-plane shutter does. Like most daguerreotype pictures, it was a mirror image, reversed left for right.

|

| FRIEDRICH VON MARTENS = Panorama of Paris, 1846 |

Thanks for the post. Presumably the plate could be curved because it was made of metal. Do you know of any attempts to create curved plates once they moved to glass negatives?

ReplyDelete