Camera Obscura

Camera Obscura

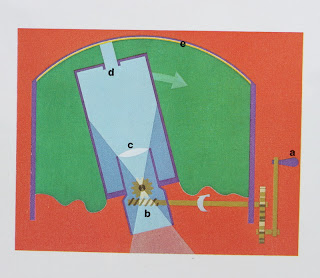

Many artists of the 17th and 18th Centuries used a camera obscura for precise preliminary sketches for paintings of landscapes, buildings and even portraits. The portable model shown above worked exactly like the modern reflex camera. Light entering through the lens was reflected by an angled mirror inside the box; the mirror projected a riqnt-side-uo image on the ground-glass screen at the top, which was shielded from surrounding light by a folding hood. The artist placed a thin piece of paper on the glass and traced the image, achieving perfect perspective with a minimum of effort.

Instamatic Camera

The camera, oddly enough, was invented many centuries before photography. In the form of the camera obscura, it projected a view of an outdoor scene into a darkened room, directing light rays from the scene through a small hole in one wall to form an image on the opposite wall. During the 11th Century a number of Arabian scientist-philosophers were amusing themselves with camera obscuras made out of tents. In the late 15th Century Leonardo da Vinci described the "dark chamber" in knowledgable detail.

When one of Leonardo's countrymen, a Neapolitan scientist and writer named Giovanni Battista della Porta, became interested in camera obscuras toward the end of the 16th Century, he reacted as millions of amateurs have ever since: he got a camera of his own. He experimented with a lens to sharpen the image and then invited some of his friends in for a show. Seating them in the room facing away from the aperture, he uncapped the lens. On the wall could be seen a group of actors hired to play a little drama outside. Della Porta's guests, unhappily, were not amused by his motion picture show; the sight of tiny human forms cavorting upside down on a dark wall sent them into panic. Not long after, their host was brought before a Papal court on a charge of sorcery; he somehow wriggled out of the trouble, but found it prudent to leave the country for a while.

By the end of the 17th Century camera obscuras were serving practical ends. They were made in the form of movable chambers and sedan chairs so that artists could carry them around, get inside, and trace landscapes and cathedrals in accurate perspective, using translucent paper placed over a ground-glass viewing screen. One of the first fully portable models was designed by Johann Zahn, a German monk. Zahn's camera, a wooden box nine inches high and two feet long, had not only a lens that could be moved in and out in a tube to focus the image, but an adjustable aperture to control the amount of light entering the box and a mirror that cast the image, right side up, onto a translucent screen on top so that it could be viewed from outside the box. Zahn's device was identical in principle with the modern single-lens reflex camera and had he had some kind of light-sensitive plate to put into it he would have invented photography.

However, virtually nothing was known about photographic chemicals at the time and it was not until 1826 that a French lithographer-inventor, Joseph Nicephore Nlepce, applied recent discoveries about light-sensitive compounds and finally supplied the missing element. Niepcs coated a sheet of pewter with an asphalt solution, inserted it in an artist's camera obscura much like Zahn's and placed it on his windowsill. After an exposure of eight hours he succeeded in making the world's first photograph: a dim, fuzzy image of his farmyard in central France.

After some years of effort, Niepce joined forces with a Parisian scenery designer and impresario, Louis Jacques Mande Oaguerre. Like Niepce, Oaguerre did little to improve the camera, but he did find more sensitive chemicals. In 1839, after Niepce's death, he announced the first practical photographic process to the world. His daguerreotypes, which took exposures of about half an hour to produce, were surprisingly sharp. But he could photograph only still lifes, buildings and landscapes; people simply could not hold still long enough for their images to be recorded.

At the announcement of Oaguerre's breakthrough, one of the men present, an Austrian professor named Andreas von Ettingshausen, immediately recognized the problem: the crude lens Oaguerre was using was far too inefficient in gathering light (by modern standards, it had a speed of about f/17). On his return home, von Ettingshausen reported this news to his friend and colleague Josef Max Petzval, a professor of mathematics at the University of Vienna; he also introduced Petzval to Peter von Voigtlander, head of. a prestigious family optical firm. It took nearly a year for Petzval to compute the design of a new lens and have it properly made, but the result was worth the effort. Built into a special camera made for it by voigtlander, it admitted nearly 16 times as much light as Oaguerre's (its speed was about f/3.6) and reduced exposures to less than a minute.

Petzval's lens was to be the photographer's standard for 60 years thereafter. Known everywhere as "the German lens," it turned photography from a novelty into a practical craft. Thousands were produced by Voigtlander for use in his own and other cameras; and other entrepreneurs in Europe and America made many more thousands of copies. Voiqtlander soon built a second factory in Germany to handle the demand, helping to lay the cornerstone of the German photographic industry. By then, however, Petzval had quarreled with his partner, contending that he had not been properly rewarded for his achievement, and the two men split up. Although Petzval was honored later as one of the founders of photography,he died a lonely and embittered man.

The camera in which Petzval's lens was most often used was the large and heavy view camera employed by nearly all professionals and amateurs through most of the 19th Century, but now seldom seen outside the studio. It was a tripod-mounted wooden box, with another box sliding inside it like a tight-fitting drawer (later replaced by a flexible leather bellows) to move the lens back and forth for focusing. The photographer adjusted focus while looking at the image on a ground-glass screen in the back; the screen was removed and replaced with a plate holder for picture taking.

With the introduction of faster plates in the late 1870s, the camera needed a new element: a mechanical shutter that could dependably produce exposures in fractions of a second. The first shutters were not built inside the camera, but were accessories that the photographer fitted over the front of his lens. One, the "guillotine," or drop shutter, was the essence of simplicity: a sliding board with a rectangular hole in it. When the photographer released the shutter, the board dropped, letting light pass through to the lens during the instant the rectangle moved past. Rigged with rubber bands, this type of shutter permitted photographers like Eadweard Muybridge to stop a horse in mid-gallop with speeds of close to 1/S00 second. The first focal-plane shutter, which operated like the guillotine but had an opening of adjustable size, was used by a British photographer named William England as early as 1861. The other main type, the leaf shutter, was first introduced by Edward Bausch in 1887.

By the 1880s a variety of ingenious special-purpose cameras also appeared: giant cameras to produce giant prints (enlarging was still impractical); multi-lens cameras that could record many small, inexpensive portraits on a single plate; stereo cameras that created an illusion of three dimensions; panoramic cameras that took in broad views. But all of these devices were still too unwieldy and expensive for most amateurs. Also, with few exceptions they still involved the loading, unloading and developing of one plate at a time. Then, in 1888, a single event launched photography on its way to becoming a hobby for everyone: George Eastman, a former bookkeeper in a Rochester, New York bank, announced his Kodak No.1, the first true hand-held camera designed to use roll film.

The Kodaks were aimed at the snapshot market; the dream of a small yet versatile camera for serious photography was still unfulfilled. In the spring of 1925, however, a handy little camera was displayed at the Leipzig Fair. Made by the German optical works of E. Leitz, it was called the Leica (from "LEitz CAmera"); it used a roll of 3Smm film to provide 36 exposures; it had a fast focal-plane shutter and a high-quality f/3.S lens.

The Leica had started as a gleam in the eye of Oskar Barnack, head of Leitz's experimental department, some 20 years before. Barnack, whose health was poor, was nevertheless an avid hiker and amateur photographer and liked to pursue his pastimes O,n Sundays in the Thuringian Forest. After panting up and down hills with his S x 7 view camera and a suitcase full of equipment, he began to dream of a camera he could simply put in his pocket or sling from his shoulder. Barnack’s idea –“kleines Neqativ, grosses Bild" ("small negative, large picture") started to take shape. At first he tried cutting his 5 x 7 plates into small pieces and usinq them in an experimental camera, but the tiny negatives were too coarse to produce decent enlargements. Later, when he started working for Leitz on a motion-picture camera, he thought of using that camera's film, which was specially prepared to record fine detail in a small negative.

The film made the difference and the Leica in its later form set the standard for the modern hand camera that could take almost any kind of picture under almost any conditions. One lever advanced the film and wound up the mechanism of the focal-plane shutter, which could give any of a range of exposures from one second to 1/1000 second. The extremely fast lens (now f/1.9) permitted picture taking indoors without special lighting and a rangefinder mechanically connected to the lens provided accurate focusing. Most important, the camera was so small and simple to use that it could be taken anywhere and operated without fuss.

Barnack's Leica revolutionized photography. Along with similar precision cameras like the Ermanox (page 164) it became the new tool of photojournalists as well as an increasing number of amateurs, who prized its ability to catch unposed, natural pictures. And in turn such photographers began to support an ever-growing market for other types of small, versatile cameras, each with its own distinctive advantages. The twin-lens reflex, which enabled the photographer to focus through a separate lens coupled to the taking lens, was made popular by the introduction of the Rolleiflex in 1927; and in 1937 the Exacta provided a versatile small camera that could be easily focused through the taking lens, the 35mm single-lens reflex.

These and subsequent developments in fine cameras have been spectacular enough, but the real camera explosion has come since World War II with. the astonishing success of two families of cameras for the amateur: the Kodak Instamatics and similar "do-everything-for-you" cameras of other manufacturers, and the Polaroid Land Cameras, named for Edwin H. Land, inventor of the first successful in-the-camera developing process. (Land was inspired to create the picture-in-a-minute camera by his small daughter:

When he was taking snapshots of her one day, she impatiently asked how soon she could see them and was heartbroken when he explained about the delay involved in developing and printing.) Both these families of modern cameras give the photographer the simplicity that won amateurs to George Eastman's first Kodak. Film magazines snap into place so that there is no threadihg. Light-sensitive devices gauge illumination and automatically set shutter or aperture for exposure. Fine focusing must still be done by the human eye-but the inventors are working on that problem too.

Petzval's Lens (Voigtlander)

Petzval's Lens (Voigtlander)

Petzval's Lens (Voigtlander)

Petzval's Lens (Voigtlander)

Voigtlander Modern

Voigtlander Modern

Voigtlander Modern